In response to the recent publication of Elizabeth Winkler’s lively and thought-provoking Shakespeare Is a Woman and Other Heresies, which is, among other things, a powerful book-length argument for academic freedom in English departments, Slate.com published a review by staff writer Isaac Butler labeling Winkler’s book “Shakespeare Trutherism” and urging a supposedly long-overdue full stop to Shakespearean authorship studies. Or, as the title of Butler’s review grumbles, It Is Long Past Time to Retire the Oldest, Dumbest Debate in Literary History.

The reason the debate may actually be the dumbest is because one side argues the way this title and the review itself argue, pretending there’s nothing to debate. Unfortunately for the intellectually curious, the truly dumb (read, willfully incurious) side comprises the academic gatekeepers. Doubting “the Bard” is a surefire way to avoid hiring or career advancement in traditional English departments and publishing houses. But the authorship of the Shakespeare canon is far from being a settled matter. The deeper scholars outside the academy dig into the question, the shakier the orthodox case inside looks.

Butler is a prime example of the weakness and laziness, even, of Shakespearean orthodoxy. He begins his review with a few paragraphs summarizing what “we know” about William Shakespeare:

He was born in April of 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon. His father, John, was a leatherworker who held several municipal offices in their hometown, including burgess, alderman, and high bailiff. William married a woman named Anne Hathaway who was pregnant on their wedding day in November 1585, a common occurrence at the time. Their first child was a daughter, Susanna; they then had twins, Hamnet (who died young) and Judith. At some point, William made his way to London, where he became an actor and shareholder in the Globe Theatre. We know the William Shakespeare of Stratford is the same William Shakespeare of the theater in London because in 1596 he renewed his father’s previously unsuccessful application for a coat of arms and the title of gentleman, and it was granted sometime in the next couple of years. In 1602, a list of people whose coats of arms were perhaps too generously bestowed was drawn up by the York Herald, and the list included a sketch of the Shakespeare coat of arms attributed to “Shakespear ye Player by Garter.” Shakespeare of Stratford’s last will and testament also includes a bequest to his partners and fellow actors at the Globe.

This litany of facts omits some of the unflattering bits about what we know of William of Stratford’s life: the several lawsuits of neighbors in his home town and in London over trivial sums over the years; the fine he was ordered to pay for hoarding grain during a public emergency (i.e., the plague); the eyebrow-raising reference in the will to the “second-best bed” being left to his wife, with the remainder of the estate going to his daughter Susanna, who had married a Stratford physician. No mention in the will, as might be expected of a professional author, of papers or precious books. Butler doesn’t linger on the peculiarity that the mention of the Stratford arriviste‘s coat-of-arms in the York Herald calls him a “Player” but makes no mention of his being a playwright or poet. Would being an actor have mattered more to the greatest author in the English language than the claim to fame his writing brought to him? Would his being an actor have mattered more to his contemporaries? Ben Jonson and the publishers of the First Folio surely didn’t think so.

Nevertheless, Butler soldiers on making a few leaps, gliding right past the shakiness of evidence for his claims:

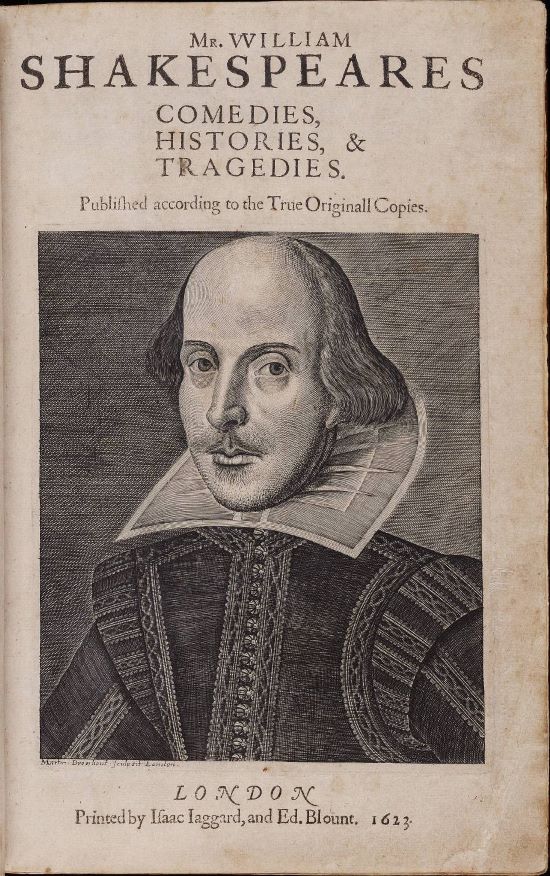

We also know that William Shakespeare wrote plays and poetry. During his life, over a dozen plays were published with Shakespeare as the attributed writer, as were his poems “The Rape of Lucrece,” “Venus and Adonis,” and “The Phoenix and the Turtle,”as well as his sonnets. Documents from the time list him as the writer of additional plays that were not published with his name on them (publishing a play without a credited author was a common practice). The company in which Shakespeare was a shareholder and actor performed these plays. In a set of popular satires called the Parnassus Plays, performed between 1598 and 1602, Shakespeare was identified as an actor-poet, quoted frequently, and mocked mercilessly. In 1623, after Shakespeare’s death, his plays were collected by people who knew him into an omnibus called Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, which we generally refer to as the First Folio.

The most egregious leap is the first sentence in that paragraph. You have to buy it to buy the rest of Butler’s assertions. But this is the crux of Butler’s insistence that the debate is the “dumbest” in literature. If his facts were irrefutable, yes, it would seem really dumb to challenge them. But they are not solid facts. The key word in the Stratford man’s defenders’ case is “attributed”: His name is on some of the published works. (Of course, Donald Trump’s name is on the work attributed to him, The Art of the Deal, but does anyone still think he wrote a single word of it?)

The fact is, we do not know if Will of Stratford wrote anything in his life. The only clear evidence we have that he ever even touched a pen are the six shaky signatures, with five different spellings, on his will and other legal documents.

Can a person who had evident trouble holding a pen and spelling his own name really have written Hamlet, not to mention the rest of the Bard’s canon?

Most educated people know not everyone believes that the bald-pated man in tights from Stratford-upon-Avon whose face is plastered all over anything to do with the Bard is the actual author of the plays and poems. One of my middle school teachers (it may have been a French teacher, actually) told us that some people, including Mark Twain, believed Francis Bacon was the actual author and had hidden his name in the lines of a sonnet.

This arcane knowledge didn’t change my perception of the authorship question much at the time, when I was just getting a handle on the world and not yet interested in digging under newly acquired appearances. Why would a writer go through the elaborate trouble of hiding his name in his verses, I wondered? Why not just go with a simple by-line that lets everyone know immediately whose words they’re reading, as every other author does? It’s that naive question that has saved Stratfordian orthodoxy’s bacon (so to speak) over the decades and permitted them to utter “Occam’s razor” as their get-out-of-scholarship-free card.

In my twenties, I borrowed from the library an intriguing-looking, brand new book, The Mysterious William Shakespeare by Charlton Ogburn. I’d only had time to read half of it before I had to return it, but Ogburn’s devastating puncturing of the Stratford myth was enough to thoroughly convince me that Will of Stratford seemed too preoccupied with money and status to waste time acquiring the extraordinarily deep learning and rich life experience necessary to write these brilliant works of literature. (If you’re interested in the numerous reasons to doubt, I recommend another brilliant, brutal take-down of the Stratford myth: Diana Price’s Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography, which compares what we know about Shakespeare to what we know about his peers. The paucity of the former is truly shocking.)

A few years later, I bought Ogburn’s book (at Shakespeare & Co. in New York, of all places) and read it cover to cover. I was persuaded by Ogburn’s passionate, scholarly argument to believe the author behind the name is probably Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. I have excellent company. Among those who have shared this belief are Sigmund Freud, David McCullough, Jeremy Irons, Derek Jacobi, Mark Rylance and at least two late Supreme Court Justices. These are not dumb people.

Winkler is anti-Stratfordian, but not necessarily Oxfordian. Her book, unlike the 2018 Atlantic article it expands upon–that piece focused on the case for Emilia Bassano, a poet who some also consider a candidate for “dark lady of the sonnets“–doesn’t argue for a single author. The value of this book is in the way Winkler opens up the floor for debate, challenging readers of all persuasions to ask questions they may not have thought to ask. Was Shakespeare a woman? Would that explain the unusually profound understanding the author shows the female characters of the plays, the prescient (by several centuries) application of the Bechdel test to several of the most important plays?

To answer the many interesting questions she has about the authorship issue, Winkler enlists the help of a fascinating, distinguished group of scholars from all points of view, including some of those who attacked her for daring to write her original article.

The orthodox are hardest to enlist, perhaps not surprisingly. The pope of Stratfordian orthodoxy, Sir Stanley Wells. former editor of the Shakespeare Department at Oxford University Press and chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon, cancels his appointment to be interviewed at his home in the cheesy tourist trap town where the “Birthplace” Trust sits the day before when he learns that Winkler is author of the disturbing article suggesting Shakespeare might have been a woman. Nevertheless, she persisted, and Wells finally agrees to a contentious meeting that resembles a Congressional hearing (lots of “I don’t remembers” and “I was not awares”). Harvard’s “charismatic” Stephen Greenblatt, celebrated author of Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, is difficult to pin down, but he eventually consents to a Zoom meeting during which he seems to take a step back from ultra-orthodoxy and allow that questioning received wisdom can sometimes be a good thing. He ends the interview after 20 minutes, pleading a sudden more pressing matter. James Shapiro, author of Contested Will, never replies to Winkler’s requests.

Perhaps because I agree more with them, or because they agree with Winkler, the interviews with the anti-Stratfordians, particularly Oxfordian Alexander Waugh and Marlovian Ros Barber, are especially delightful highlights of the book. The overall effect of reading these probing scholars’ provocative ideas, I was surprised to learn, was that I sensed my beliefs shifting somewhat over the course of the book. I don’t pretend to be a Shakespeare scholar myself. I am persuaded by careful and compelling arguments. To now, the most persuasive ones I’ve found come from researchers like Ogburn, Waugh, Roger Stritmatter, Katherine Chiljan and other scholars associated with the DeVere Society in the U.K. and the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship in the US.

But Winkler’s book has made me consider that the Shakespeare of the plays may not have been a single author but, rather, a group of the most talented poets and playwrights of the time–and there were many extremely talented men and women writing in Elizabethan England when Oxford was. (According to Winkler, even some Stratfordians are moving in the direction of believing their man probably collaborated with other authors on some of the plays, at least.) It seems plausible to me that Oxford was the center of this group, perhaps the editor in chief, as well as one of the primary authors. Many clues suggest his prickly relationship with the Queen and her Lord Treasurer, Robert Cecil, (who, not incidentally, was Oxford’s guardian and father-in-law), influenced not only the themes of several of the plays but also the manner in which they were written. For example, might the mysterious annuity of £1,000 that the Queen authorized for Oxford have been payment for a poetic enterprise Oxford spearheaded (to coin a phrase) involving the patriotic production of the history plays to propagandize the legitimacy of the House of Tudor and its domestic and foreign policy agenda? Might Oxford have relied on a crew of fellow playwrights he’d already been working with to hammer out a steady flow of these works?

Who knows? But aren’t these interesting kinds of questions any lover of Shakespeare should be encouraged to ask and investigate? Is there no room in the academy for this kind of scholarship, or are all Shakespearean scholars doomed for all time to pretend there’s no point digging too deep into the obscurity of history because the “natural genius” of a Stratford bumpkin is sufficient to explain the majesty, depth, reach, and lasting power of this complex canon?

How about reading Francis Bacon’s Contribution to Shakespeare (Routledge, 2019) which gives another side to the argument.